How can we make better strategy?

At Firetail, we spend a lot of time thinking about how organisations interested in social progress should think about ‘strategy’.

When we talk to Chief Executives about strategy, we consistently hear the following questions:

How should we set strategy in a world that seems to be changing quickly?

How could we approach long-range strategy differently?

How can we connect the insights in our strategic plan to our daily decisions?

What’s different about strategy for social progress and purpose-driven organisations?

We decided to bring people together through a series of articles and events to consider these questions - looking to the future, exploring specific challenges, and seeking insights from our clients’ experiences.

This first article is a survey of the latest thinking about strategy. It attempts to address why so many people are frustrated with their current approach to strategic plans, and what to do about it.

Most of this literature is aimed at strategy for commercial organisations, so our following article focuses on the particular challenges of strategy for social progress. We will look at questions of values and purpose, collaboration and participation, impact and innovation, new power and new networks.

We will also consider where the models we describe below are helpful, and where they aren’t. Future articles will focus on making strategy happen, and what we might do to tackle some of these issues.

What’s the problem with strategic plans?

Chief Executives and Strategy Directors agree that their 3- to 5-year ‘strategic plan’ doesn’t always seem like a useful tool for leading their organisations.

Yet everyone does them. At Firetail, we have supported the creation and implementation of dozens of strategic plans throughout the years in many different sectors and contexts. We have first-hand experience of their strengths and their limitations.

Strategic plans are useful in lots of ways. They are statements of direction and ambition that help to tell the story of an organisation, the change it wants to see and the role it wants to play.

Done well, the process of putting a strategic plan together is valuable. The best leadership teams use the process as an opportunity to challenge themselves, to reflect, to talk to important stakeholders, revisit old assumptions and look at the world around them. They set or re-affirm their values and inspire their teams.

The main flaw of traditional strategic planning is that it promotes an approach to strategy as something the organisation - and often only the leaders of an organisation - ‘does’ every few years.

In a changing, competitive world, it becomes less relevant over time.

When the underlying assumptions change, the strategic plan becomes obsolete.

In an environment where change is the only constant, organisations need to respond with continuous adaptation and innovation to stay relevant, effective and impactful.

From ‘strategic planning’ to ‘strategic thinking’

Strategy should go beyond the process of developing a strategic plan.

The document you produce is probably the least interesting part of a good strategy.

A good strategy is about connecting a point of view to an organisation’s objectives, and ultimately people’s day-to-day work.

Many traditional strategy tools, like SWOT, the BCG matrix and Porter’s Five Forces were designed at a time when the world was more stable, or at least one in which strategic decisions could set your direction for a few years at a time.

But they don’t produce surprising insights, tell you what to do, or what to think. In a SWOT, every strength is also a weakness, and every threat an opportunity.

Contemporary approaches emphasise ‘strategic thinking’. They put more emphasis on insight, adaptation, responsiveness, innovation, and creating synergies with operations.

Our clients understand that this shift needs to happen. They recognise the difference between strategic plans and strategic thinking. But often strategy is led by the operational processes set up to support periodic planning (like informing budgeting cycles and resulting in annual plans) - not with the aim of enabling continuous reflection.

People end up with bad strategic plans by default. They use the processes and tools they always use. The challenge is stop and think what it really means for an organisation to think strategically.

New frameworks for strategic thinking

As we have thought about this problem, we have found the following frameworks, books and articles useful to encourage this different way of thinking:

1. Thinking strategically: Where should we play and how will we win?

Strategy tools and frameworks need to be dynamic, and help to generate surprising and useful insights.

The academics Roger L. Martin and Richard Rumelt both agree that strategy is about making choices. They have developed useful models to help organisations make those choices.

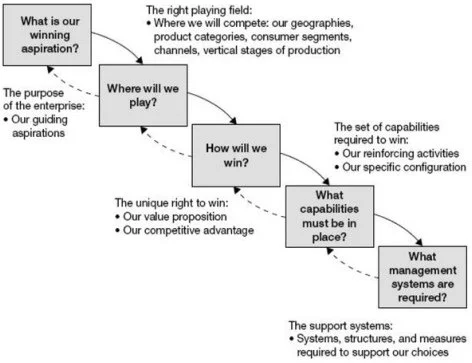

Roger L. Martin’s “Cascading strategic choices” lets organisations ask themselves reflective questions about aspiration, place in the market, approach and how to get there.

Organisations need a culture that embeds continuous reflection on these questions, and appropriate adaptation.

It’s designed primarily for commercial organisations, but Martin has written extensively on social enterprise and finds this way of thinking applicable in most contexts.

Cascading strategic choices, Roger L. Martin

Along the same lines, Richard Rumelt argues that ‘good strategy’ is coherent action backed up by an argument: a combination of thinking and acting.

“Despite the roar of voices equating strategy with ambition, leadership, vision, or planning, strategy is none of these. Rather, it is coherent action backed by an argument. And the core of the strategist’s work is always the same: discover the crucial factors in a situation and design a way to coordinate and focus actions to deal with them”.

He argues that the ‘kernel of strategy’ has three elements: a diagnosis that defines or explains the nature of the challenge, a guiding policy for dealing with the challenge, and a coherent set of actions designed to carry out the policy.

As most challenges are unlikely to remain unchanged within the life span of a strategic plan, this calls for an adaptive approach.

Rumelt’s book is the best, most accessible guide to modern strategic thinking.

Further reading:

2. Scenario planning: How can we think about the future?

The world is changing rapidly and unpredictably, and this needs new responses.

Scenario planning was originally developed in the oil industry, to give them a framework for making investments that would take decades to pay back. Today, it’s a useful tool for thinking about change on a much shorter timeline.

If done right, scenario planning and horizon scanning can generate the insights you need to feed an organisation if it is going to think strategically. We have seen good scenario planning exercises result in changed focus, approach and operating model.

Scenario planners think about the world as ‘VUCA’ - Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous (others use ‘TUNA’ - where ‘Volatile’ is replaced by ‘Turbulent, and ‘Complex’ by ‘Novel’).

As with most strategic processes, the output of a scenario planning exercise is less important than the process. Rafael Ramirez and Anna Wilkinson at the University of Oxford describe scenario planning as “a method for direction-finding and strategy formation that defines itself by non-prediction”.

It lets organisations reflect on the messy effects of the future, and the implications of different framings of an uncertain situation.

It also provides a common language for a group considering the challenges ahead. This can be particularly powerful when trying to plan for collective impact.

Scenario planning has its limits. Whilst it should give you a framework for considering different ways forward, you can’t turn a scenario for the world into a budget for your organisation and nor should you try,

The common challenge in a scenario planning exercise is that organisations don’t know how to translate these into strategic and organisational things to do. With an inability to act, these insights risk being shelved.

In our own experience, working with the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC), the scenario planning exercise to create the “Future of the Chemical Sciences”, informed both the Society’s strategy and led to a number of new initiatives, such as addressing the lack of diversity and inclusion in the chemical sciences through initiatives such as the ‘Breaking the Barriers’ report. The approach Firetail designed was covered in the MIT Sloan article below.

Further reading:

Firetail and the Royal Society of Chemistry: Future of the Chemical Sciences

Firetail and the Royal Society of Chemistry: Breaking the Barriers

MIT Sloan Management Review: Using scenario planning to reshape strategy

3. Lean strategy: How do they do it in Silicon Valley?

If you’ve been in a meeting where someone has talked about a ‘minimum viable product’ or ‘product-market fit’, then you’ve been listening to someone influenced by the book “The Lean Startup” by Eric Ries.

Whilst the ‘lean’ concept was initially developed in manufacturing, it has become popular as an approach to strategy in Silicon Valley.

The book suggests that a dynamic approach, through constant experiments of innovation and integrating adaptive feedback loops, is the best way to create successful and sustainable businesses, products and organisations.

Ries argues that testing how well different things work is better than doing too much up-front hypothesising and theorising about what will work best. The aim is to put something in front of a customer as soon as possible, and develop a strategy based on those insights, with constant experiment and iteration.

A feedback loop of ‘Build-Measure-Learn’ lets organisations continuously see what’s working, enabling dynamic adjustments to their offer, processes and approaches.

Amazon is an ideal example of how a lean, iterative, approach to strategy can contribute to building a successful organisation. In 2004, Amazon was selling books and DVDs and was worth $18bn - half the value of eBay at the time. Today, it is valued at over $900bn. The emergence of Amazon Prime through a series of experiments and iterations was central to this success.

15 years later Amazon Prime has completely changed consumer psychology and behaviour and dominates online retail.

The continuous experimentation, learning, investment and iteration made Prime a success, but the upfront financial analysis suggested Prime was a terrible idea that could be the end of Amazon.

The biggest challenge in this model for purpose-driven organisations is that there is often no market to establish product-market fit. Yet many of the lessons of quick launch, not overthinking things, rapid iteration and data-driven feedback are highly applicable.

Further reading:

4. Strategy palette: What’s the strategy for your strategy?

One reason organisations end up with bad strategic plans is that they default to the process that they always follow. They don’t ask themselves whether a different approach might be better.

In strategy, context matters.

Different organisations operate in different types of environments.

These environments pose different challenges and change at varying speed. Organisations are able to influence or control them to varying degrees.

Designing an approach to strategy based on your circumstances might seem obvious, but almost no-one does it. One size does not fit all.

Organisations should choose an approach to strategy (a strategy for the strategy) that matches the specific demands of the environment.

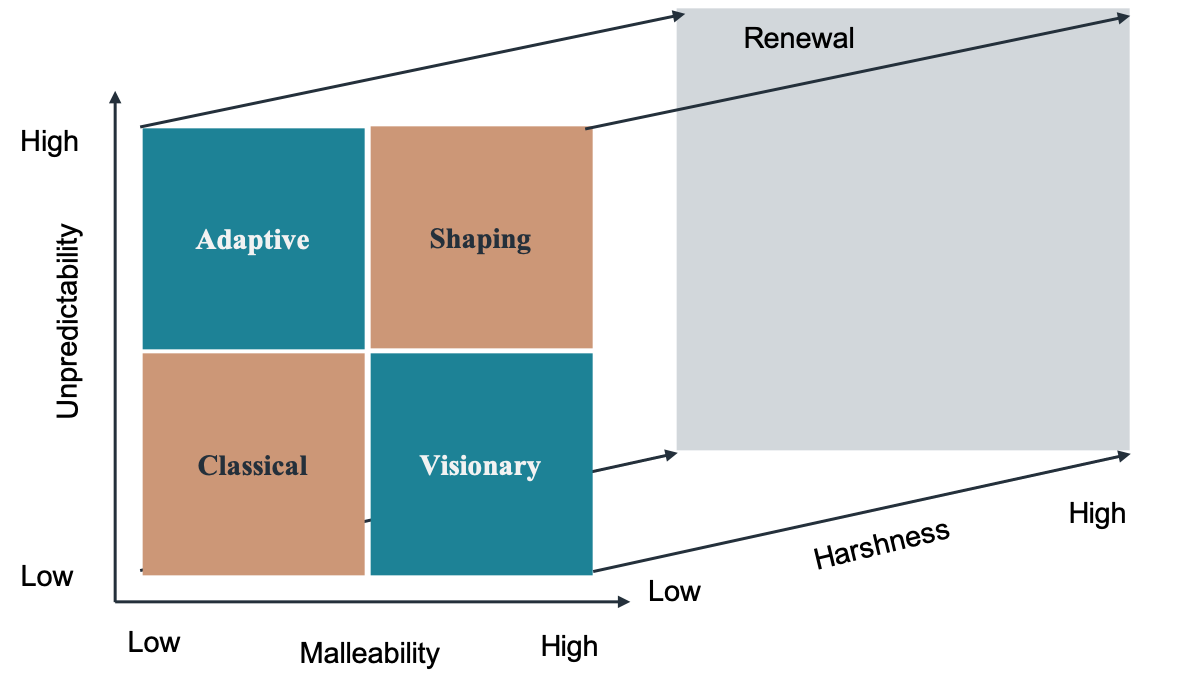

Martin Reeves argues that we can use a simple framework to identify five strategy environments that comprise ‘the strategy palette’.

Environments differ along three axes: predictability – the extent to which you can forecast it; malleability – the extent to which you can shape it; and harshness – the extent to which you can survive it.

These reveal five different environments as seen in the figure below, each requiring a specific approach to strategy.

The Strategy Palette, Martin Reeves

The classical environment is highly predictable but difficult to change. The stable environment allows for comprehensive analysis and longer-term planning with the aim to scale, differentiate oneself from the competition, and develop the capabilities needed to succeed. Many traditional tools (SWOT, Porter) were developed for this environment.

This type of rigorous analysis and planning does not work in the low predictability / low ability to change, adaptive environments. Here, flexibility is key. Approaches and tools like those proposed by Rumelt, Martin and Lean strategy are useful in this environment.

Gaining first-mover advantage is the key to success in visionary environments, which is predictable but where organisations have an opportunity to shape it. With a known objective, strategists can predict the path to realisation, and plan deliberate actions to achieve it.

The shaping environment is hard to predict but organisations have a high opportunity to shape it. Activities and stakeholders can be orchestrated to shape a sector to their advantage. While the other environments concern individual organisations, the shaping environment is about ecosystems – as such it is equally about collaboration and competition.

Finally, in the harsh renewal environments, organisations have come out of step with their environments and need to transform in order to be viable and competitive. This is about survival. By reinventing their business and operating model, and focusing activities to conserve and free up resources, they have a chance to survive. Only when this first phase is done and the organisation is viable, can they go on to choose one of the other four approaches.

The challenge is to choose the right approach, in the right part of the organisation, at the right time. Organisations must stop to reflect about things such as known/unknown unknowns, and what it needs the strategy to do in order to succeed.

Failing to do so can lead to the pitfall of falling back to static and overly simplistic strategy tools (like SWOT) that merely take what is already known into consideration. The result will be strategic plans that are not fit for purpose.

Further reading:

What next?

If this article has a conclusion, it is that organisations that have a ‘good strategy’ have a culture that embeds the process of generating insights, making choices and executing them well.

They are clear about the questions they are trying to answer, aware of the context they are working in and deliberate in the tools they choose, the people they engage and the way they communicate.

This is all strategy is. Coherent action backed by an argument.

The big question for us is how applicable these models can be for organisations pursuing social progress. What does product-market fit look like when there’s no market? How do you win when you are trying to inspire collaboration? How do you even know you are winning? Where do values fit in these approaches? How do you bring people together in forming strategy? What’s the right organisational form?

These also inspire questions about governance, leadership and the specific challenges of making strategy happen. These questions and more will be covered in future articles.

Hopefully, this has sparked your thinking on the future of strategy. We will convene a series of events over the coming months to discuss these questions. If you are interested in participating, or have any questions or comments about this article, feel free to get in touch via mail@firetail.co.uk

By Andy Martin and Maria Beradovic

With thanks to Peter Grigg, Malcolm Spence and others for their feedback on earlier drafts.